During the long French summer of 1937 the marriage of close relatives, Pinot Noir and Gamay, was officially consummated with a new AOC. Since then, Bourgogne Passetoutgrain has been the standard bearer and sole guardian of this sometimes uneasy union. I say “uneasy” because the original cahier des charges has changed very little in the first 85 years, compared to its two Swiss counterparts—Salvagnin of Vaud and Dôle of Valais—which are very much changed from the original.

The story of Salvagnin was told earlier in this blog, and, sad to say, is no longer a Pinot Noir and Gamay blend. Instead, Salvagnin represents the sort of forgettable blend of multiple grapes with no consistency or discernible character.

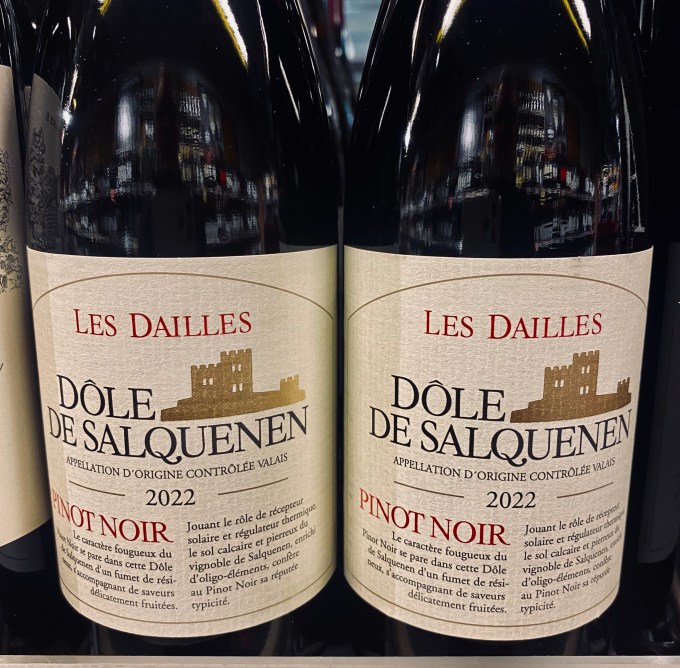

Dôle, on the other hand, still pays lip service to its origins and history as a popular workhorse blend. According to Swiss wine writer, Alexander Truffer, Dôle is one of the most recognizable names in Swiss wine, surpassing even the iconic wine region of Lavaux in terms of consumer awareness. It remains a staple in the cafés and bars around the country and is one of the leading SKUs in the wine aisles of Swiss supermarkets.

But, lately, its continued existence as an important “brand” and cultural touchstone is in doubt. It is in danger of going the way of Salvagnin.

The French Connection

The name Dôle is believed to come from the French city of Dole1, the birthplace of Louis Pasteur and erstwhile capital of Franche-Comté. It is situated on the Bresse plain northwest of the main Jura vineyards, 155 kilometers from the Swiss city of Geneva. In its mid-19th century form the city was surrounded by vineyards, more than 20,000 hectares of them, with dozens of both common and rare varieties spread among them. Today, the vineyards number a mere 2100 hectares, with none around the town itself, and only five varieties allowed within the various AOCs.

The 18th and 19th centuries also marked an era of robust exchange between the vineyards of eastern France and western Switzerland. According to Charles Rouget in his book Les vignobles du Jura et de la Franche-Comté (1897) there were more than 200 hectares of the well-traveled Swiss variety Chasselas in the Jura.

More surprising, perhaps, was the presence of the rare Valais native, Rèze, though it was known as Petit Béclan Blanc at the time. The interaction between the two camps may explain why the low-profile Valais specialty Vin de Glacier, formerly made from Rèze, developed in a style reminiscent of Jura’s Vin Jaune. In any case, Rèze remains experimentally in the Jura as a potential climate change hedge.

There is also evidence that a Jura bio-type of Pinot Noir known as Savagnin Noir or Salvagnin Noir made its way to Neuchâtel at around the same time the Burgundian bio-type Servagnin was flourishing. The names Salvagnin and Servagnin became interchangeable, while the former was the name given to the Vaudois blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay mentioned earlier.

Of course, the most celebrated shared variety is Savagnin, which is grown throughout western Switzerland, but is best known in Valais as Heida or Païen. It was thought to be less well adapted to other parts of Switzerland, but Jean-Denis Perrochet of La Maison Carée in Neuchâtel scoffs at the suggestion. He believes Savagnin may have pre-dated Chasselas in the vineyards there and argues that it is ideally suited to the marginal climate along the shores of Lake Neuchâtel. Its early presence in Neuchâtel has yet to be proven, however, but given the cross border exchanges already noted, he may be on to something.

Gamay from Dole

In the late 18th century another grape of note is known to have made its way from Jura’s vineyards to Geneva’s famed botanical garden. The garden, under the direction of the legendary Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, included Gamay vines from Dole.

Why would a Gamay from Dole be of interest to Swiss growers when Gamay from Burgundy and Beaujolais was already present in the vineyards of western Switzerland? The answer may lie in Gamay’s ability to adapt to local conditions. The Gamay bio-type, Plant Robert, for instance, is a well-known example of a uniquely Swiss adaptation. Might the Gamay from Dole have already included adaptations desirable to Swiss growers? We may never know the answer, as I am unaware of any surviving accessions in Switzerland. Unfortunately, de Candolle’s astounding collection was lost.

Whatever the attributes of Dole’s Gamay might have been, it’s notable that the name Dôle stuck as the preferred synonym for Gamay in both Geneva and Vaud.

The home of Augustin Pyramus de Candolle in Geneva’s Old Town.

The Valais Years

Gamay first appeared in Valais in 1854, six years after the arrival of Pinot Noir and roughly 40 years after the appearance of Dole Gamay in Geneva. The first recorded use of the term Dôle in Valais was shortly thereafter, but, confusingly, not as a synonym for Gamay, but for Pinot Noir, instead. Apparently, Valais never got the memo that Dôle was already being used as a synonym for Gamay by its neighbors to the west.

Since inception, Dôle was understood to be either pure Pinot Noir (hence the confusion), or later, Pinot with increasing amounts of Gamay. It was the unregulated upwards drift of the Gamay component that finally compelled officials in 1941 to legislate that Pinot Noir must always dominate the blend. This was one of the first pieces of legislation designed to protect wine quality before the establishment of AOCs.

Still, the confusion over nomenclature persisted. At the beginning of the 20th century there was even a clumsy attempt to rechristen Gamay as Grosse Dôle and Pinot Noir as Petite Dôle. Finally, common sense prevailed and each variety assumed its prime name, while the name Dôle became exclusive to Valais as the name of a wine.

The decades prior to 1941 were essentially unregulated with respect to Dôle. The 1941 legislation stipulated that Dôle must be either pure Pinot Noir or a Pinot-dominant blend with Gamay. 1991 marked the creation of the Valais AOC which included the 1941 definition for Dôle. This was modified again in 1993, but with more clarity: Dôle must be either pure Pinot Noir or 85% Pinot Noir and Gamay with Pinot dominating, and, for the first time, a small allowance of 15% was made for other reds.

| Pinot Noir-Gamay AOCs through the Years | 1st Generation | 2nd Generation | 3rd Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passetoutgrains | 1937-1943: Minimum 20% Pinot Noir and 15% Gamay; Maximum 15% other co-planted varieties. | 1943-2009: Minimum 25% Pinot Noir and 15% Gamay; Maximum 15% other co-planted varieties. | After 2009: Minimum 30% Pinot Noir and 15% Gamay; Maximum 15% other co-planted varieties. |

| Salvagnin | 1949-1960 (no AOC): Pure Pinot Noir (Servagnin) or with Gamay (not regulated). | 1960-2009: Pinot Noir and Gamay (regulated but no AOC until 1995). | After 2009: Any of the 31 red varieties permitted by statute without minimum or maximum. |

| Dôle | 1941-1993: Pure Pinot Noir or blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay with Pinot dominant. (regulated but no AOC until 1991). | 1993-2021: Pure Pinot Noir or minimum 85% Pinot Noir and Gamay with Pinot dominant; Maximum 15% other reds. | After 2021: Pure Pinot Noir or minimum 51% Pinot Noir and Gamay with Pinot dominant; Maximum 49% other reds. |

New legislation in 2021 marked the beginning of the end for Dôle as we know it. Under the new regulations Pinot Noir could be as little as 26% of the final blend. Statute 916.142 of the Ordonnance sur la vigne et le vin (OVV) Section 8.2, Article 55 established that Dôle can be either pure Pinot Noir or 51% Pinot Noir and Gamay with Pinot dominating. The allowance for other reds ballooned to 49%. Thus, a theoretical Dôle might be 49% Other reds, 26% Pinot Noir and 25% Gamay—a far cry from its original form.

Where Are We Now

To be fair, not all of the changes to the Dôle brand are attributable to commercial pressures. Some of the change is logistical. Since the establishment of Valais’ AOC, plantings of Pinot Noir have shrunk 30%—from 1732 hectares in 1991 to 1275 in 2023. Gamay has suffered a 50% decline—from 984 hectares in 1991 to 457 in 2023. Meanwhile, consumer perception of Dôle as an inexpensive blend remains unchanged, which makes Dôle unsuitable for higher value native varieties. The same is true for what remains of Pinot Noir, which routinely commands a higher price as a mono-varietal than it can as a Dôle blend.

That leaves “new” grapes like Gamaret, Divico, Ancellota, Diolinoir, and Carminoir to carry the load. The typical result from blending with these new grapes is a deeper, darker, more structured Dôle with less of the lift provided by Pinot Noir and Gamay. Some will argue that overall quality is improved, and in some cases that may be true, but the character of the wine is completely different. The silly 51% threshold seems to be designed as a concession to tradition, but, in reality, it’s the only thing that distinguishes Dôle from an ordinary assemblage.

And where does this leave the three communes which boast Dôle as a Grand Cru? According to the same statute, Section 11, Article 93, Part 4, a Grand Cru red can only be made from Pinot Noir, Gamay, Syrah, Cornalin, and Humagne Rouge. This means the currently fashionable 49% other reds are banned from Grand Cru bottlings. Such a restriction might make Dôle Grand Cru unsustainable.

Stay tuned. I expect more legislative adjustments to come and none of them will please traditionalists.

1 There is no circumflex in the spelling of the city, Dole. Dôle may reflect an older spelling retained by the Swiss. Dole = city in France; Dôle = first, synonym for Gamay; then, the name of a wine.

Discover more from artisanswiss

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hello Dennis,

Thanks, very interesting as usual. I have a question: Is the Swiss Valaisan ‘vin de glacier’ related to the French ‘vin de glace’, which I believe is a Burgundy specialty?

Hope all is fine with you , look forward to getting together in June

all the best

Ulrika

LikeLike

No. Vin de Glace is Ice Wine. Literally wine made from late harvested grapes that are frozen on the vine. Very sweet.

Vin de Glacier is wine that is aged in barrels that are not topped up and thus age oxidatively, similar to sherry. The barrels are stored up the mountain from Sierre at elevation. Very rare and not offered to the public. They are family treasures.

LikeLike