In my opinion, the canton of Geneva is the most complicated and frustrating wine region in Switzerland. To be sure, many great wines are made here by supremely skilled artisans, but there are still too many sub-standard wines born out of complacency and lack of inspiration. It seems that while the rest of Switzerland is reinvigorating its winemaking heritage, a significant part of Geneva remains committed to an outdated polyculture model. The irony of course is that polyculture is a great thing and something more farmers should strive for, but all too often in Geneva the advancements in organic and biodynamic farming and minimal intervention winemaking are met with skepticism by an aging cohort. It follows that enlightened winemaking is not the priority it should be.

Another part of the problem is deeply rooted—literally. Holdover varieties like chasselas and gamay continue to dominate the landscape. Statistics over the last ten years are revealing: In 2013 chasselas and gamay accounted for 49% of the Geneva vineyard. Today the number is 40%. That’s progress, but not enough if the goal is to attract new consumers. To young Genevans with cash to burn papi’s wine is ringard.

It turns out it’s not just the younger consumer rejecting grandpa’s wine. I am reminded of a wine bar that opened near my home several years ago. It boldly promised to offer nothing but Geneva wine— now it trades exclusively in cheap Italian imports. Admittedly, 25% of the canton’s population is transient or foreign born and may not include many dedicated locavores, but the coup de grâce is that Geneva wine is mostly an afterthought for rest of Switzerland, too. The prestigious Mémoires des Vins Suisses, a collection of some of Switzerland’s best wines, lists only three Geneva wines among its core selection of 60 labels.

There was hope that a new variety developed in 1970 would serve to diversify the Geneva vineyard—and perhaps even become a much needed signature grape—but gamaret and its twin, garanoir, have been stuck in neutral for more than a decade. In 2013 there were 120 hectares of gamaret—ten years later the number is the same. Garanoir, to its credit, has eked out a gain of three hectares, from 45 to 48 over the same period, but, as the numbers suggest, both lack pizzazz.

There are signs that things are beginning to change. Generational succession has sparked a renaissance at several wineries. The common thread between them—surprise—is an emphasis on organic or biodynamic farming and a shift towards natural winemaking. When this occurs the target market changes. Suddenly younger consumers are engaged, restaurants and wine bars that evolve from the change are packed with new fans, notoriously jaded palates are energized by new discoveries, and a trickle of foreign buyers starts poking around.

Many of these younger winemakers are cutting their teeth on the “Three Gs” and they are doing it in style. PetNats and zero-zeros are slowly finding their way onto some of Geneva’s top wine lists. Several wine shops dedicated to natural wine have opened recently and naturally made gamay is a conspicuous presence in all of them.

These new upstart wineries will only add to a solid core of winemaking excellence. We’ll have to wait for the rest.

A Short History of Geneva Wine

There is evidence that wine culture in what is now Geneva is among the oldest in Switzerland, predating the Roman conquest of 121 BC. The inhabitants at the time, a Celtic tribe known as the Allobroges, were quite spread out. In fact, back then Geneva (Genaua) was a mere outpost located far from the larger settlements of Vienne (Vienna) Lyon (Lugdunum), and Grenoble (Cularo).

In the 1st-century AD, Pliny the Elder wrote of a local wine known as “picatum” made from “Allobrogica” which scholars today believe was mondeuse. A more likely story is that Allobrogica was a basket of grapes—the so-called “proto-mondeuses”—or precursors of mondeuse and its purported relatives, the sérine biotypes. Because most vineyards were co-planted with multiple varieties until relatively recently (the late 19th-century), the “basket-of-grapes” theory makes the most sense.

In any case, it’s well known that mondeuse, both red and white, and altesse once flourished in the Geneva vineyards, leaving us to speculate that gringet, roussanne, savagnin, mollard, persan, and poulsard, might have thrived there as well. After all, Geneva’s on-again, off-again connection to Savoie allowed for much cross-pollination and its roots as an Allobroges settlement suggest it shared a parallel viticultural patrimony.

In a twist of irony, the decidedly Swiss grape gamaret is now permitted in Beaujolais and the Ain region of France where it can be included in the IGP Vin des Allobroges.

The Current State of Play

Today, the vineyards of Geneva cover nearly 1350 hectares, accounting for 5% of this tightly packed canton. It is the third largest wine region in Switzerland—fourth, if you consider Deutschschweiz as one entity, as many do.

An Overview of the Geneva Vineyards

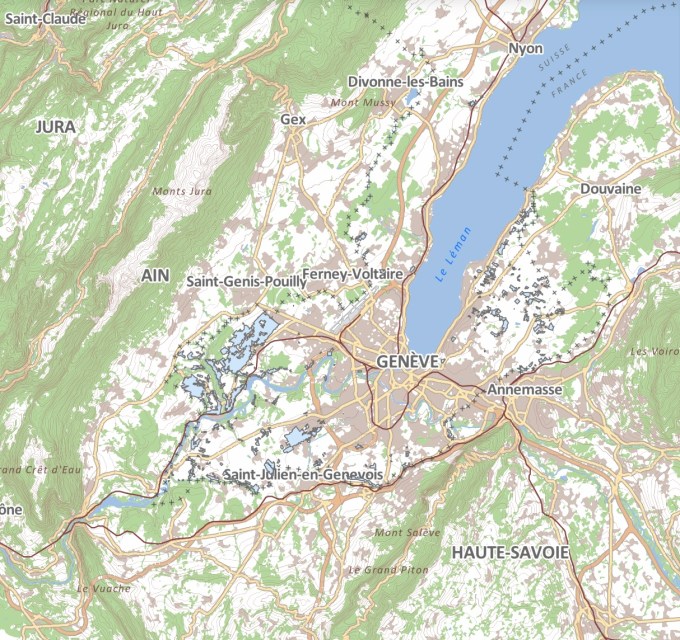

The canton is divided into four wine areas that are fixed by political and geographical boundaries: the rive droite (the area west of the Rhône river, also known as the Mandement); entre Rhône et Arve (the area between the Rhône and Arve rivers); entre Arve et lac (the area between the Arve and the lake); and the zones franches (the free zones). The vineyards of the free zones are owned by Swiss growers but located across the border with France. The wines made from these border vineyards are entitled to the Geneva AOC so long as they are made within the canton.

The commune of Satigny on the rive droite holds the distinction of being the largest wine commune in Switzerland. It is also one of the best. The communes of Russin and Dardagny, next door, round out the majority of the rive droite vineyards. The three together form a dense carpet of vines that slopes gently to the south and southwest all the way to the river’s edge.

The entre Rhône et Arve vineyards are concentrated in the commune of Bernex and the villages of Lully and Laconnex. There are also important vineyards in the communes of Soral and Bardonnex to the south, along the border with France. These are more gently sloping vineyards than in the rive droite and are in closer proximity to the city center.

The entre Arve et Lac vineyards are spread out and interspersed with residential zones, orchards, and mixed crops, most of which are destined for processing into seed oils. This is where polyculture is greatest and wine quality is most uneven. Many plots are west to southwest facing with a few facing northeast and northwest. Many are flat or very gently tilted. The Coteau de Choulex, Château du Crest, and the Coteau de la Vigne Blanche make the best wines.

The rive droite and entre Rhône et Arve Vineyards (left) and Entre Arve et Lac Vineyards (right)

In addition to the Geneva AOC, there is a Premier Cru classification available for wines that come from permitted vineyards in any one of 22 lieu-dits or villages. There is a separate cahier des charges in effect.

Unfortunately, the words Premier Cru on a bottle of Geneva wine is no guarantee of quality. Some of these vineyards are so small that only a couple of growers might have access to the vines, which diminishes the likelihood of finding a good wine. I don’t pay much attention to this classification. As usual, the best indication of quality is to know who made the wine.

The 22 Premier Crus are listed in the table below:

| AOCs of Geneva & 22 Premiers Crus | Coteau de Bourdigny (Satigny) RD | Coteau de Choully (Satigny) RD | Château de Choully (Satigny) RD | Coteaux de Peney (Satigny) RD | Coteau de Peissy (Satigny) RD |

| Côtes de Russin (Russin) RD | Coteau des Baillets (Russin) RD | Coteaux de Dardagny (Dardagny) RD | Coteau de Genthod (Genthod) RD | Coteau de Collex (Collex-Bossy) RD | Coteau de Bossy (Collex-Bossy) RD |

| Coteau de Lully (Bernex) ER et A | Côtes de Landecy (Bardonnex) ER et A | Rougemont (Soral) ER et A | La Feuillée (Soral) ER et A | Coteau de la Vigne Blanche (Cologny) EA et L | Coteau de Chevrens (Anières) EA et L |

| Coteau de Choulex (Choulex) EA et L | Château du Crest (Jussy) EA et L | Mandement de Jussy (Jussy) EA et L | Domaine de l’Abbaye (Presinge) EA et L | Grand Cara “Carraz” (Presinge) EA et L | Geneva AOC |

L’Esprit de Genève

Back in 2004, sluggish sales demanded a new plan of action. In a vinous version of “when life gives you lemons. . .” the trio of gamay, gamaret, and garanoir were reimagined as the city’s signature blend, complete with a fancy package and a catchy name: L’Esprit de Genève.

The name hearkens back to an essay written in 1929 in praise of the city’s international mission by Swiss novelist Robert de Traz. L’Esprit de Genève, he said, reflects the values of humanism, social justice, independence, and peace, as espoused by three of its most famous former residents—Jean Calvin, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Henri Dunant.

The aim was to associate the wine with Geneva’s international brand and to confer upon it immediate respect. 20 years later, it’s up to the drinker to decide how it has measured up.

A Tasting Opportunity

Recently, I traveled to Zürich to attend a blind tasting of the new L’Esprit de Genève collection from 2022. For those not paying attention, I had to travel all the way to Zürich from my home in Geneva to taste the emblematic wine of Geneva. So much for organized marketing campaigns. It’s also an indication that the seemingly impenetrable Swiss-German market needs special attention.

Vintage 2022 enjoyed a remarkably uneventful growing season after the meteorologically disastrous 2021. The grapes ripened evenly and fungal diseases were virtually non-existent.

The Esprit de Genève charter is slightly more stringent than AOC or Premier Cru requirements, but no more than what a diligent winemaker would require on his own. Below are its most important elements:

| L’Esprit de Genève Charter | Ripeness | Yields | Alcohol | Wood Regime | Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The blend shall include a minimum of 50% gamay and 20% gamaret and/or garanoir, with a maximum of 20% other varieties | Minimum 85º Oeschle for the gamay and 90º Oeschle for the rest | Yields of not more than 50 hectoliters per hectare | Alcohol levels of at least 12.5% | An unspecified percentage of the components must be aged in wood | The color must be deep with notes of purple and a minimum color intensity of 9.00 |

The last requirement appears to be highly subjective and lightly enforced. A few of the samples presented failed to meet this color test, at least to my eye.

The logic behind the blend is to create a greater whole—where the red fruit, spice, and acidity of gamay is enhanced by the color, weight, and structure of gamaret. Indeed, when handled well, the blend can work as designed.

Anyone who complies with the charter can use the label and benefit from the marketing. In 2022 there were 18 different expressions from 18 different wineries. I narrowed my list to five favorites.

My least liked wines are any combination of aggressively herbal, too tannic, too acidic, too woody, too thin, too bitter, and/or too extracted. There are 7 in this group.

The middle group of wines is just that, middling. There is nothing inherently wrong with any of them, but each lacks one or more of the positive attributes mentioned below. There are 6 in this group.

My favorites all share the pleasing ripeness typical of a dry and sunny growing season. They are for the most part balanced, textured, complex, and delicious; and they are poised for positive development. In the end, my favorite wines represent good value, as well. All are priced between 21 and 25CHF.

Not a bad price for a signature wine from a place with a 2000 year history of winemaking.

Artisanswiss Top 5

| (1st—17.5 points) Domaine Les Hutins, Dardagny |

A quick word on my top wine: Domaine les Hutins is an outstanding family winery located in the rive droite vineyards of Dardagny. Gamay is a speciality here and when sourced from it’s jewel-like La Briva parcel of old vines it can rival cru Beaujolais. This EdG bottling was rich and fat with a bit of char from the oak. It has a pleasing earthiness, ostensibly from gamaret, and a fragrant nose of bergamot peel in slowly simmering berry compote.

| (2nd tie—17 points) Domaine Les Vallières, Satigny / Domaine de la République et Canton de Genève, Lully |

| (4th tie—16.5 points) Domaine de la Printanière, Avully / Château des Bois, Satigny |

Vinum Magazine Top 5

| (1st tie—17.5 points) Domaine les Hutins, Dardagny / Domaine Villard et Fils, Anières |

Vinum note: More intense color and more marked legs. An elegant nose combines elderberry jam, a hint of violet, medicinal herbs, and a hint of chalk. On the palate, it appears round, charming, a little warm, with slightly toasted notes. Substantial tannins and noble bitterness hold it together in the finish. A wine that does everything just right. (My translation from French)

| (3rd tie—17 points) Domaine de la Printanière, Avully / Cave de Sézenove, Bernex |

| (5th tie—16.5 points) Domaine de la République et Canton de Genève, Lully / Château des Bois, Satigny / Domaine de Beauvent, Bernex / Domaine de la Vigne Blanche, Cologny / Domaine de la Mermière, Soral / Domaine de La Guérite, Gy / Domaine des Graves, Avusy |

Discover more from artisanswiss

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another wonderfully informative piece. I’m pleased to see Les Hutins mentioned as I do know their wines reasonably well.

There was a time when the coop at Satigny showed signs of stirring into life but that was a few years ago at least and I’ve not visited them since.

LikeLike

Thanks David.I’ll have to check on the Coop in Satigny. There might be some treasures there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another wonderfully informative piece. I’m pleased to see Les Hutins mentioned as I do know their wines reasonably well.

There was a time when the coop at Satigny showed signs of stirring into life but that was a few years ago at least and I’ve not visited them since.

LikeLike