Any discussion of the rare Swiss grape Amigne should begin with a mention of its longtime home, Vétroz. This nondescript village of 6400 residents boasts 174 hectares of vineyards — 102 of which are planted on terraces supported by exquisitely crafted dry-stone walls (Fig. 1). More than one-third of this privileged portion is devoted to Amigne. That’s a lot of civic pride and community resources invested in one, relatively unknown grape. But Vétroz is so linked to Amigne that its caretakers have doubled-down by creating an association of growers to promote it, and a conservatory of accessions to preserve and study it. To be sure, there’s plenty of Pinot Noir, Gamay and Chasselas in the rest of the commune, but Amigne belongs to Vétroz, and to no one else.

Amigne: From Whence It Came

Local advocates insist that Amigne came to Valais with the Romans 2000 years ago. Ancient artifacts uncovered nearby attest to an early Roman presence, but no proof is offered that they brought Amigne with them. Vétrozians cite references to the Roman variety (or varieties) Aminea in Columella’s first century agricultural treatise, De Re Rustica, as proof of Amigne’s early presence in Valais; but others counter that Amigne is merely an etymological derivation of Aminea and not proof they are one and the same.

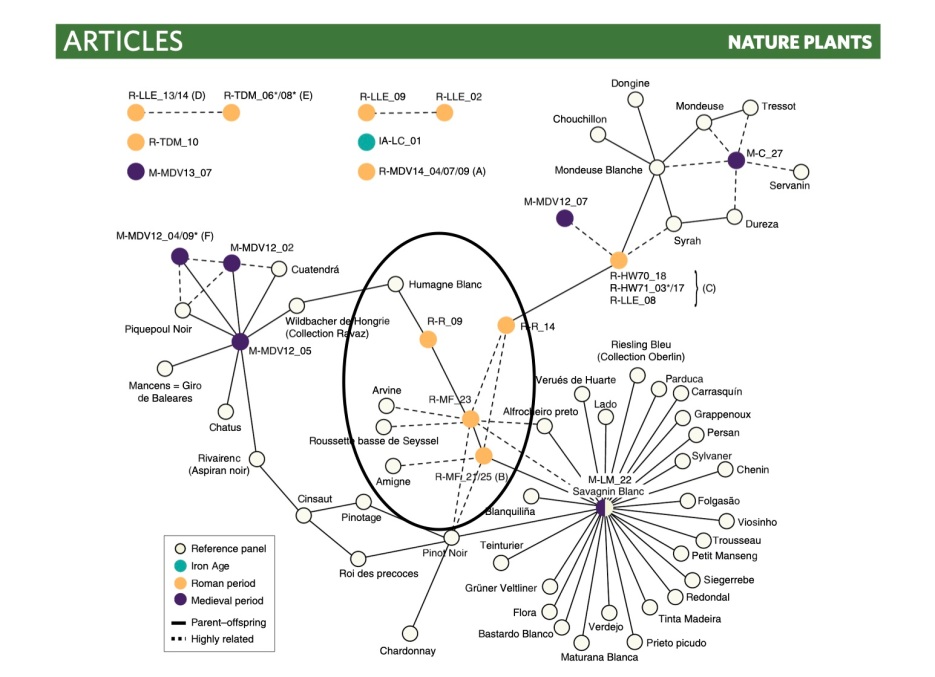

More convincing is the recent discovery of several Roman settlements in France (Montferrier and Roumeges in Hérault). Several grape pips found there are from unidentified varieties that display direct genetic relationships (perhaps parent-offspring) to three key Alpine varieties. One of the pips, known as R-MF 21, is from the first century and is directly related to Amigne. Two others, R-MF 23 and R-R 09, are directly related to Arvine and Humagne Blanche, respectively. If these “precursor” varieties are in fact Roman, then the on-again, off-again belief that they are responsible for Amigne’s presence in Switzerland gains credibility.

One of the early sceptics, Dr. José Vouillamoz, says as much in an article for the Swiss wine club, DIVO:

“These discoveries shake whatever doubts I had, long expressed in my capacity as a Swiss ampelographer, on the Roman origin of Valais grape varieties . . . In light of the study’s results, several previously questioned hypotheses, may have a basis in fact.” (translation mine).

While a Roman origin for Amigne now appears likely, there is still no proof it came to Valais 2000 years ago. There is a gap of 1500 years between the appearance of the precursor in Montferrier and the first mention of Amigne in Valais in 1686. It’s possible Amigne was brought to Valais some time after the Roman conquest, or, the variety uncovered in Montferrier was crossed with another unknown variety later in Switzerland.

The solution to this puzzle may be forthcoming. Several unidentified grape pips found at Gamsen/Waldmatte in Valais (800-500 BC) may offer more clues as to the exact origin of these Swiss varieties, but DNA analysis is required. Until then, the mystery of the origin of Amigne and other Valais natives remains.

Soils

There is another intriguing twist to the Hérault/Vétroz connection — both vineyard areas are based on the platy rock formation known as schist. In Hérault, there are various forms of it present in the vineyards, but, in Vétroz, it’s predominately a single type of black-colored schist composed of clay and limestone. Is it possible the Romans found schist to be the preferred base for Aminea and/or Amigne?

The Vétroz schist is distinguished by a covering of glacial till from both the Rhône and Derborence glaciers. This stony top layer is interspersed with a flaky, relatively fine layer of decomposed schist, which, because of its dark color, is able to store heat during the day. This has a salutary effect on the vines, particularly late in the season when evenings begin to cool in earnest. It is also a characteristic of clayey schists to store water between layers, which is vitally important for nutrient assimilation in this dry area.

Whatever questionable impact schist has on the aroma and flavor of wine, there is no question its physical properties are beneficial to the vine and perhaps crucial in this otherwise difficult landscape.

So What Is Amigne Like?

Perhaps, the biggest issue with Amigne — aside from its scarcity, of course — is the question of style.

Dry Amigne is a new style that is poised to reverse the previous generation’s preference for doux (lightly sweet) and flétri (sweet) styles. Unfortunately, the dry style has suffered in the marketplace because of consumer frustration with a lack of information. Which is dry, and which is sweet? The Groupement des Encaveurs solved this problem with a simple graphic that depicts three bees — one highlighted bee represents a dry wine of less that 8 g/l of residual sugar; two highlighted bees represents a lightly sweet wine between 9-25 g/l; and three highlighted bees represents a sweet wine of more than 25 g/l.

At harvest, growers aim for readings between 105º-110º Oechsle, which means for dry Amignes elevated alcohol levels — mostly between 14% and 15% — are the norm. Dry examples are strong and powerfully scented with notes of fruit confits — notably apricot and mandarin — honey, orgeat, marshmallow, and white chocolate. Ironically, Amigne is not the type of wine to make one think Alpine. There’s nothing particularly fresh, light, or minerally about it. Acidity levels are well below those of Completer, for instance, with just enough tang to balance the rich fruit flavors, high alcohol, and somewhat perceptible tannins in the finish.

I love the texture of Amigne, whatever the style. It reminds me of a mouthful of cashews — rich and creamy with a slight chalky grit.

Amigne is a vigorous variety that is susceptible to both shatter (coulure) — the spring föhn is a particular nemesis — and shot berries (millerandage). It ripens late, three weeks after Chasselas, and, like Completer, can be left to hang beyond physiological ripeness because of its thick skin and loose clusters. Rot is usually not an issue, so excellent sweet wines without the complexifying effects of botrytis are routinely made.

The Vignes de Prieuré Conservatory

Currently there are nine members of the Groupement des Encaveurs who are responsible for maintenance of the Vignes de Prieuré conservatory. The conservatory is a 7000 square meter parcel dedicated to research. Half of it is planted to several dozen accessions of Amigne; some of them sourced from heritage vines scattered throughout the canton and some from backyard arbors that were previously unidentified. Preserving the genetic diversity of the variety, which was almost wiped out with phylloxera, is just one goal of the conservatory.

There is also important work to be done regarding rootstocks, trellising, and yields, with a special emphasis on the development of natural solutions to the problems of millerandage and coulure. There is also a program of massale selection which seeks to identify and propagate those vines with desirable traits.

Amigne will never be widely available, but the Groupement is dedicated, nonetheless, to communicating the virtues of this local speciality. With the kind of refinements they are seeking through research and a future emphasis on dry wines, there is likely to be more improvement and a bit more visibility ahead.

Discover more from artisanswiss

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.