Each year the Fête de la Nature invites the public to reconnect with nature via an ambitious schedule of hikes, lectures, hands-on activities, and guided tours to parks and nature reserves that collectively celebrate the diversity of Switzerland’s natural wonders. This year I participated in the program Les Perles de Zeneggen organized by the Musée du Vin and led by geologist Thomas Mumenthaler, a key contributor to the iconic book on Swiss vineyard geology, Roche et Vin.

The “pearls” in this case are the tiny vineyards of Zeneggen. There are two of them, Riedboden and Im Waldji, both precipitously inclined on the slope like pearls on a pendant, but because they are so tiny and isolated they mostly go unnoticed by passers-by below.

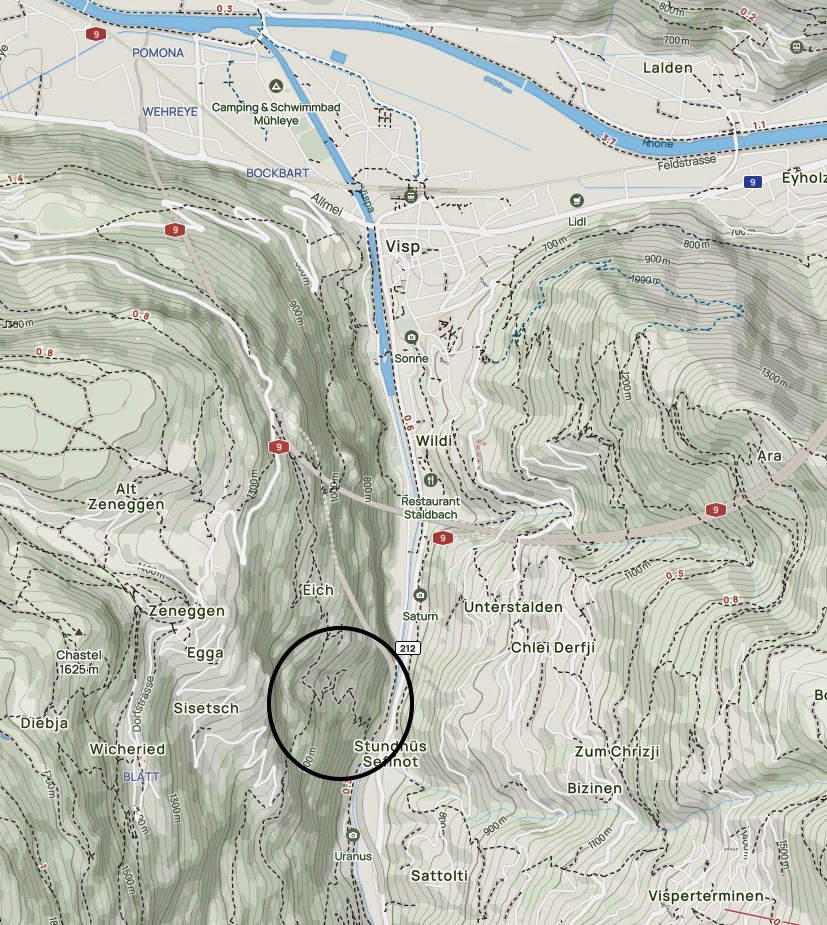

The Vispertal is a lateral valley of the upper Rhône Valley of Valais, and its river, the Vispa, is a major tributary of the Rhône River as they merge near the city of Visp. The valley is best known as the gateway to Zermatt and the home of Visperterminen, a neighboring wine village boasting Switzerland’s highest vineyard.

What makes Zeneggen special in this already heady environment is its unique geology. It is one of only three vineyards in Switzerland situated on volcanic rock, and the only one of the three based on the striking green rock known as serpentinite.

As romantic as it may sound this outcropping of volcanic material was not the result of a volcanic eruption but was formed deep within the earth 300 million years ago before the process of uplift and erosion exposed it to the surface.

The Zeneggen vineyards: note the different rock between the middle right (serpentinite) and top left (schist)

A serpentinite block shoring up a terraced parcel in Riedboden

According to geologist Alex Maltman in his book Vineyards, Rocks, & Soils, serpentinite is a “beguiling rock” that “comes about from the metamorphism of the magnesium-rich olivine in rocks like peridotite, which change to the sheet mineral serpentine.”

In other vineyard landscapes around the world serpentinite is considered inhospitable to the vine and to vegetation generally. When it is present it is usually associated with barrenness or stunted growth.

“The problem for grapevines,” he explains, “seems to be the preponderance of magnesium in the soils, which can lead to low uptake of the nutrients calcium and potassium, coupled with toxicity arising from the relatively high levels of nickel, cobalt, iron, mercury, and chromium.”

Deficiencies in calcium and potassium not only negatively affect the health of the vine but also the resulting wine—the main culprits being elevated pH levels and oxidation. In addition, serpentinite soils are often thin and stony, and unlike other volcanic soils, lack water-retaining properties. Irrigation is often necessary.

Sounds pretty damning, but as far as I know the Zeneggen parcels are immune and do not require supplemental treatments of calcium or potassium. This may be due to the steepness of the vineyards and the tendency of some magnesium compounds to run-off due to high water solubility.

Thin stony soil is slick with poor water-retaining capacity.

The Hike

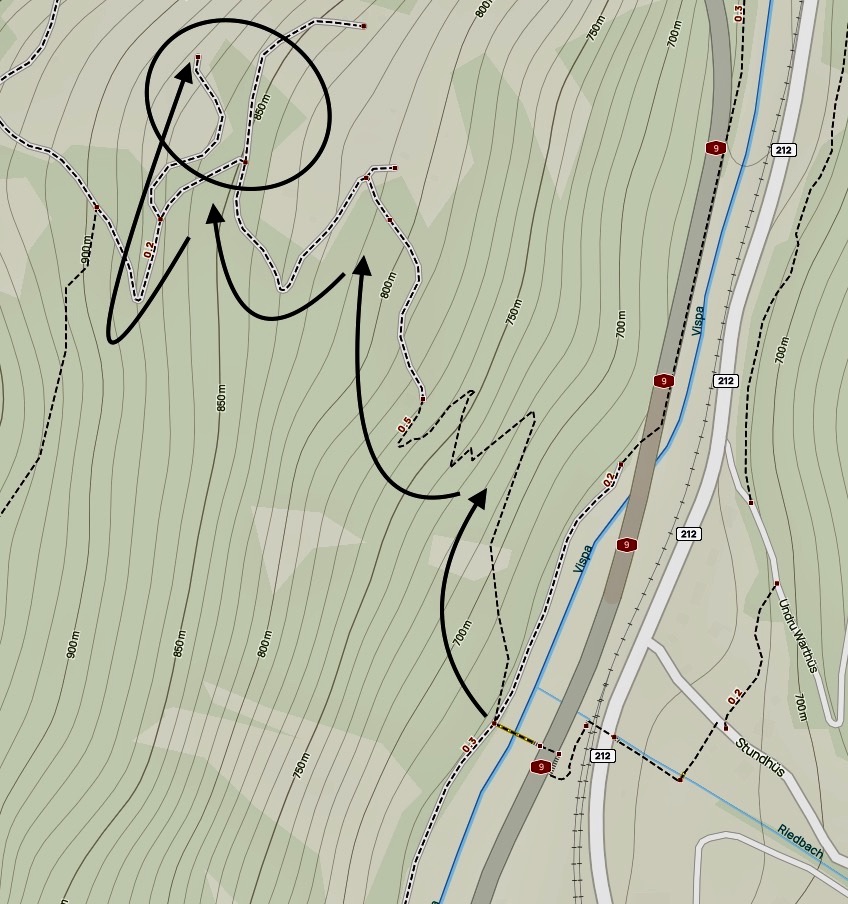

In order to reach the Zeneggen vineyards there is a small service road for workers, but for the rest of us there is a network of trails from the valley floor. On this particular day, the trails were a featured attraction.

First, a caveat: when a Swiss person tells you a hike is moderately difficult, don’t believe them. Or, at least be skeptical and expect something more than moderate. In my case, it wasn’t the physical exertion required that surprised me, but the narrowness of the trail and the speed at which the objects on the valley floor receded as we climbed. For those with mild vertigo, like me, this can be a problem.

The hike began innocently enough before it took a turn 50 meters in. This is where the climb really began and the trail narrowed to single file. I quickly learned to walk with my arms extended to swat away branches delivered by the person just ahead. This painful distraction was actually meditative as I delivered the same branch to the person behind. The rhythm of it allowed me to focus my attention forward and not down. As the trail narrowed further, I channeled my inner steelworker walking the high beams.

An innocent looking start

The steepest part of the climb was the last fifty meters, or so, along the perimeter of the vineyard, which led to a small terrace that my map told me stood at 900 meters elevation. This is where we were greeted by Christophe Kenzelmann, owner of the Zeneggen parcels.

Location of the hike in the Vispertal (left) and the exact route to the destination (right)

The Wines

After some introductory words by Professor Mumenthaler, Christophe spoke of his family’s involvement in the vineyards and his desire to keep going in the face of rising costs and climate chaos. Yields are extremely small and hard-earned.

There are three wines made by Christophe from grapes grown at Zeneggen: a muscat, a Johannisberg (sylvaner), and a pinot noir. They are sold exclusively at the family gasthaus, Alpenblick, and they sell out quickly, often before the end of the high season.

A perfectly nice Sylvaner hits the spot after a vigorous hike

While all are serviceable, even delicious after a vigorous hike, the real story is not the quality of the wines but the dedication required to make them. Enormous credit must be given to the family for preserving the old ways in such a harsh environment. There is nothing easy about the work required to farm this steep terrain as evidenced by the number of abandoned vineyards, some with overgrown terraces still intact, visible on both sides of the valley. It’s estimated that only 20% of Vispertal’s original vineyards are still in production today.

As for comparing Christophe’s wines to other wines grown on serpentinite in Switzerland, there is no comparison, because there are none. Furthermore, there is nothing identifiably volcanic about any of them. In that sense his wines are solid curiosities rather than compelling examples of volcanic terroir, such as those found in Sicily, Santorini, or Somló in Hungary.

The rest of the valley faces similar farming challenges but the work is done mainly on sandstone-based schist. This may be one reason why old ungrafted vines are found here. Weathered sandstone gives sandy soils which are inimical to the phylloxera louse. Keep in mind, phylloxera arrived in Valais in 1916, and in upper Valais even later, which is indicative of its isolation from the rest of Europe.

The most famous wine made in the valley is St. Jodern Kellerei’s “Veritas”, a unique expression of savagnin, or heida as it’s known locally. It is made from 100-year-old ungrafted vines located in the village of Visperterminen. It is the flagship wine of this excellent co-op which manages to take up most of the valley’s grapes.

Chanton Weine in Visp is the area’s other important winery. Its emphasis is on autochthonous and rare varieties, including himbertscha, lafnetscha, resi (réze), Eyholzer roter, plantscher (gros Bourgogne), and the famous progenitor grape, gwäas (gouais blanc).

Josef-Marie Chanton, the proprietor, is dedicated to the preservation of these native varieties which, of course, extends to his practice of preserving the heroic places from which they come. VinEsch, the non-profit he co-founded, was established to do just that.

The “pearls” of Esch, up the road from Zeneggen, are a collection of small vineyards with a documented 800-year history. In 2010 they faced abandonment because of the imminent retirement of the owner. Over the next 10 years the foundation’s members, with contributions from private and government donors, rebuilt almost 500 meters of neglected dry-stone walls while instituting a replanting campaign based on a massale selection of the best vines. The net result is 700 bottles of wine a year to benefit the work of the foundation: a white blend of completer and himbertscha, and a red blend of cornalin and an unidentified variety, presumed to be native, given the name rouge de VinEsch.

I hope this piece makes clear the scale of work involved to preserve this precious way of life against the absurdly limited output it offers. Indeed, when we talk of passion and dedication to craft there is no better example than the guardians of the Vispertal.

Hopp Schwiiz!

Discover more from artisanswiss

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nice! I hope your nerves have recovered from the walk. I did it once and I’ve never been keen to rush back and do it again, although the area is magical. I’ll post a link to this

LikeLike

Thanks Ellen. I’ve recovered now.

LikeLike