A few things coalesced to make this year’s Célébration du Non-Filtré in canton Neuchâtel a must attend event. First, it was the 50th anniversary of the initial release in 1975. That’s an amazing run for a wine that was once considered a local oddity. Second, six years had passed since I first wrote about the history and quirkiness of the event. And third, I was attracted to the venue—the city of La Chaux-de-Fonds—a curious place in the Swiss Jura I had yet to visit.

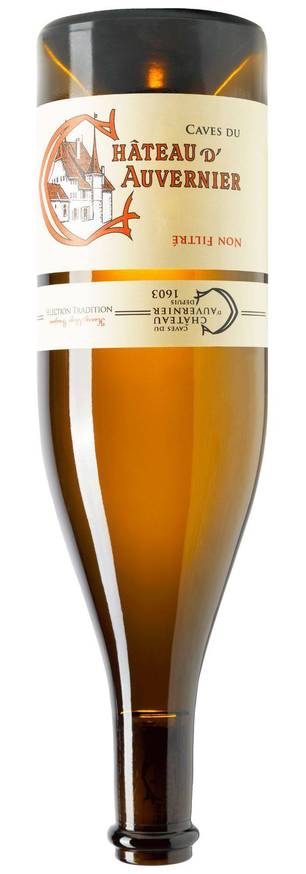

For those not familiar with Neuchâtel-style unfiltered chasselas, it’s the only wine I know of that weaves fine lees into the sensory experience. Unlike other unfiltered wines, which are left to clarify before bottling, chasselas non-filtré is bottled early with the fine lees still in suspension. The drinker is reminded of this by the upside-down positioning of the label. Once the lees are agitated the wine is ready to drink.

These days a full 15% of all chasselas grown in Neuchâtel is dedicated to unfiltered wines—with more on the way. Some optimistic growers are even devoting their entire production to the cloudy stuff.

Perhaps most startling is its resounding success in the difficult to penetrate Swiss-German market—a market which represents two-thirds of Swiss consumers. Indeed, there was a lot of scweitzerdeutsch to be heard at the event, which is a small triumph in the French-speaking west of the country. In Switzerland, all roads lead to Zürich, but the canton of Neuchâtel may have bridged the cultural gap known as röstigraben better than others.

A Curious Venue

The city of La Chaux-de-Fonds sits in a high valley between two ridges of the Jura range. To get there an almost imperceptible climb by train is required, which, weather permitting, culminates in a stunning panoramic view of the Alps across the Swiss plateau. An overwhelming feeling of isolation awaits. On the day I arrived the city seemed empty, cold, and windswept.

Isolated or not, LCdF is the historical center of the Swiss watchmaking industry and, as such, is designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. Amazingly, that lofty citation doesn’t even mention the rich architectural heritage left behind by its native son, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier. Several of his earliest works are located around town, including his residence, La Maison Blanche.

(left): La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1863 as Marx would have found it. (Zentralbibliotek Zürich)—(right): La Chaux-de-Fonds today.

The heritage citation is actually in recognition of the innovative urban-planning and subsequent reconstruction that took place after a fire destroyed most of the city in 1794. Well before Le Corbusier, of course, but perhaps an influence on his brutalist style.

The city, unlike any other in Switzerland, was rebuilt in a grid pattern with perpendicular intersections designed to resuscitate the fire-ravaged watchmaking industry. As part of the urban plan, worker’s residences were intermingled with ateliers for peak efficiency. New construction was orientated to the southeast for maximum exposure to natural light—which in turn maximized the effective working day. This purposeful reconstruction succeeded brilliantly. It propelled what was once a cottage industry into an efficient industrial machine before Henry Ford was even born.

The city’s industrial renown even attracted Karl Marx, who included his study of the division of labor unique to factory watchmaking in his seminal work, Das Kapital. 50 years later, in 1917, Vladimir Lenin was present in La Chaux-de-Fonds to address an assembly of communist sympathizers from Paris when he received word of the Russian Emperor’s abdication.

It may be coincidental, but others have commented on a distinct Soviet-era vibe to the city.

Reminding local readers of the 40th anniversary of Lenin’s visit to La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1917.

The Event

Even though no vines grow in the upper valley, LCdF has always figured in the marketing campaign for unfiltered chasselas, but only as second fiddle to Neuchâtel itself. Not surprisingly, this year’s event was a source of pride for the local community and it gave them a chance to show off the recently repurposed old slaughterhouse as an event space. It proved to be an outstanding venue.

The usual civic dignitaries and business leaders were in attendance as were several members of the electronic media, including reporters from RTS, the national television and radio network. One of them approached me for a soundbite, which you can see here, but they really came to document the growing popularity of this local product and its impact on the canton’s economy.

One reporter asked me whether I thought of unfiltered chasselas as a serious wine. My reflexive response was, “Yes, of course!”

But before I get into why I think it’s a serious wine, I should explain why I think it’s important.

Chasselas has been on a steady decline for decades now. There are roughly 2000 hectares less today than in 1994, yet it remains the cornerstone of the Swiss wine industry. That’s because more than any other variety, chasselas has benefited from the “less-but-better” quality push begun at the end of the last century. The rediscovery and redeployment of several ancient bio-types speaks to the quality commitment, as does the focus on terroir, but equally important is the successful introduction of new styles like Neuchâtel’s unfiltered version. Other styles that seem to resonate with younger consumers include natural, orange, and pet-nat. And let’s face it, younger Swiss consumers are critical to the future of chasselas.

As for market parallels, the upward trajectory of unfiltered chasselas recalls that of Neuchâtel’s other wine marketing success, œil de perdrix. Both are enjoyed all over Switzerland, but, as history has shown, both are under threat from cheap imitations. Unfortunately, like the failed attempt to trademark the name œil de perdrix, the name chasselas non-filtré cannot be protected.

It’s repositioning as a serious wine requires that it avoid the seasonality trap that plagues Beaujolais nouveau. To that end, unfiltered chasselas is now being marketed as an age-worthy wine. For the first time, organizers sponsored a tasting of older vintages as an appendage to the main event. Time will tell whether the new campaign bears fruit.

The Wines

2024 was an exceedingly difficult vintage all over Switzerland. It proved to be the second smallest harvest of the last 50 years. To illustrate, only 75 million liters were produced in 2024 versus an average of 92 million liters over the previous 10 years. Frost and hail early in the season led to poor flowering and fruit set. An abnormally cool and rainy summer led to serious downy mildew pressure, which cut yields even further.

A problematic mid- to late-October harvest made for an even shorter élévage than usual. Unfiltered chasselas must be bottled and ready for sale by the traditional release date—always the third Monday in January. As a result, fermentation aromas, which can be part of the charm, were still pronounced and some of the wines seemed disjointed.

At best the quality of the wines was uneven. Several of them displayed a lack of ripeness with the normally pleasing tropical fruit notes muted or missing. In some cases the chalky texture overwhelmed whatever fruit was present. I expect some of these wines will improve with age but my overall assessment is that 2024 was of average quality at best.

My favorite wines all displayed a fresh fruit-chalky balance that makes this style of wine so appealing. Bright notes of pineapple, mango, and passionfruit are the perfect foil for the slightly gritty texture. Among the best were the Cave des Lauriers (Cressier), Clos aux Moines (Sainte-Blaise), Domaine Saint-Sébaste (Sainte-Blaise), Domaine de Chambleau (Colombier), Chantal Ritter Cochand (Le Landeron), and Domaine de Montmollin (Auvernier).

On a sad note, missing from the event was Jean-Denis Perrochet who passed away this past summer. He was a prominent fixture at any event that promoted Neuchâtel wine and is legendary in Switzerland for his early embrace of biodynamics. I am grateful to have spent a day with him before I wrote about his beloved La Maison Carrée. He very kindly agreed to meet and taste with me very early on in my Swiss wine journey. He will be missed by his family and all who knew him.

Discover more from artisanswiss

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.