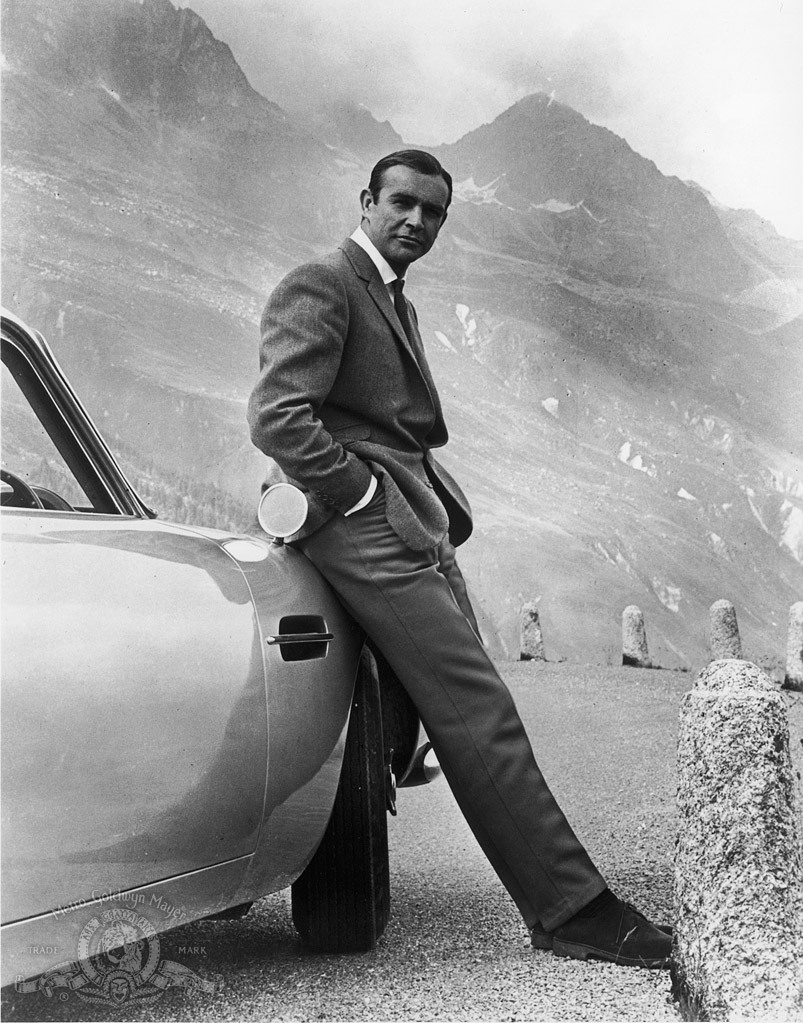

I never expected to use Sean Connery or Goldfinger as visual aids in a piece about wine, but the chase scene on the Furka Pass is just too golden — forgive the pun — to pass up. This iconic scene is instructive for two reasons: it takes us to the source of the Rhône River, one of the world’s great wine rivers, and it gives us a snapshot-in-time glimpse of a rapidly diminishing natural wonder — the alpine glacier that feeds it.

No doubt the beauty of the alpine landscape serves the film and its viewers well, but what intrigues me most is the cultural context of the river and its link to wine. Even though most wine lovers might associate the Rhône with Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage, I’m here to tell you it begins its life in Switzerland, rather humbly, as melting ice.

The Rhône is a bit different from other major European rivers in that glacial runoff is responsible for a large percentage of its flow. Indeed, 25% of its discharge into the Mediterranean is attributable to glacial melt. Upstream, before merging with its main tributary the Saône, the percentage is much higher. Further upstream, before the Rhône leaves Switzerland, it’s higher still — nearly all of its feeder torrents, including the rivers Dranse and Arve, are sourced from glaciers. The consequences of this dependence are alarming — most glaciers are expected to disappear by the end of the century. This does not bode well for the lakes and rivers of downstream Europe as all are expected to suffer significant depletion.

The Source

Because the world is getting warmer, the source of the Rhône keeps changing. It was presumed to rise from the thermal ponds at the foot of the glacier — near the now-shuttered Belvedere Hotel (header photo) — but since the foot has receded nearly two kilometers in the last century, it appears the source was hidden somewhere beneath the glacier’s massive bulk all along.

From an elevation of 1743 meters, on the Valais side of the Furka Pass, the river begins its 813 kilometer journey to the Mediterranean. 264 kilometers of that length is in Switzerland, and 150 of those are in Valais.

A leisurely train ride down the high valley offers frequent glimpses of the river as it tumbles past isolated mountain villages. As it gradually swells and gains energy it becomes clear that it has excellent hydroelectric potential. In fact, 57% of Switzerland’s energy is sourced from hydropower and the upper Rhône is a major contributor to that total.

But as kinetic as its upper reaches are, the Rhône is relatively slow-moving and lazy as it passes through the lower valley. This lazy flow and an irregular twisting path is a recipe for flooding. It works like this: the considerable agitation of sediment upstream, settles in the river’s bed downstream. When the bed is sufficiently raised by sedimentation it is susceptible to flooding; and flooding is part of the Rhône’s unfortunate legacy.

Good River, Bad River

To Valaisans the Rhône is both friend and foe. Early chroniclers reported that regular flooding occurred during the Little Ice Age (1350–1850) resulting in the episodic displacement of impoverished farmers. This was a period of social and economic instability with wealthy landowners positioned safely on the slopes while those less fortunate were left to fend for themselves.

Between 1863-1884 the first of three “corrections” of the Rhône took place. The second occurred from 1930-1960. During these periods the river’s course was straightened and fortified with levees to prevent flooding and groins to direct the flow of sediment. The taming of the river allowed for the reclamation of agricultural land from unproductive wetlands. Permanent crops and orchards replaced annual crops and the agricultural economy began to flourish. It was during this time that vineyards were crowded out by orchards and urbanization, only to be moved farther up the slope. As one of the architects of the second correction, Maurice Troillet, a Conseiller d’Etat and great uncle of famed vigneronne Marie-Thérèse Chappaz, said in an address to the Grand Conseil:

Slopes that give us unique ruby wines, sunbathed nectars that shimmer and sparkle in our glasses, and the plain and valley areas that give us milk, bread, vegetables and desserts will bestow on our beloved Valais the title of breadbasket of Switzerland.

Indeed, Valais came to be known as the California of Switzerland, supplying much of the nation’s fresh produce and a growing percentage of its wines.

Despite the advances in the controlled flow of the river, intermittent flooding continued — culminating in the floods of 1987, 1993, and the worst of the century in 2000 (Fig. 1). A third correction began soon after with funding from the federal government to supplement local resources. This ongoing, thirty-year project aims to widen the river, increase its capacity, secure the levees, and safeguard and restore native habitats.

This last bit is important.

The canton of Valais is in the midst of an environmental accounting of its public assets. It has secured and allocated hundreds of millions of francs to repair and maintain its network of dry-stone walls, its primitive but effective system of bisses (irrigation channels), and now its petulant river. All of this infrastructure is woven into the cultural fabric of the region and each plays a key role in the canton’s push to develop regional pride, economic opportunity, and tourism.

The River of Wine — Valais

The Rhône begins its run as a wine river when it emerges from the high valley at Brig. Despite some backyard parcels at Visp, the real concentration of vineyards begins at Leuk (Loèche) and Salgesch (Salquenon) and continues unabated until the river’s northern sweep at Martigny.

Vestiges of the untamed Rhône are still visible near Leuk, which is fitting since a national park, Pfyn-Finges, is located nearby (Fig. 2). This area of German speakers is known as upper Valais and pride of place belongs to the Grand Cru Salgesch designation for the local pinot noir.

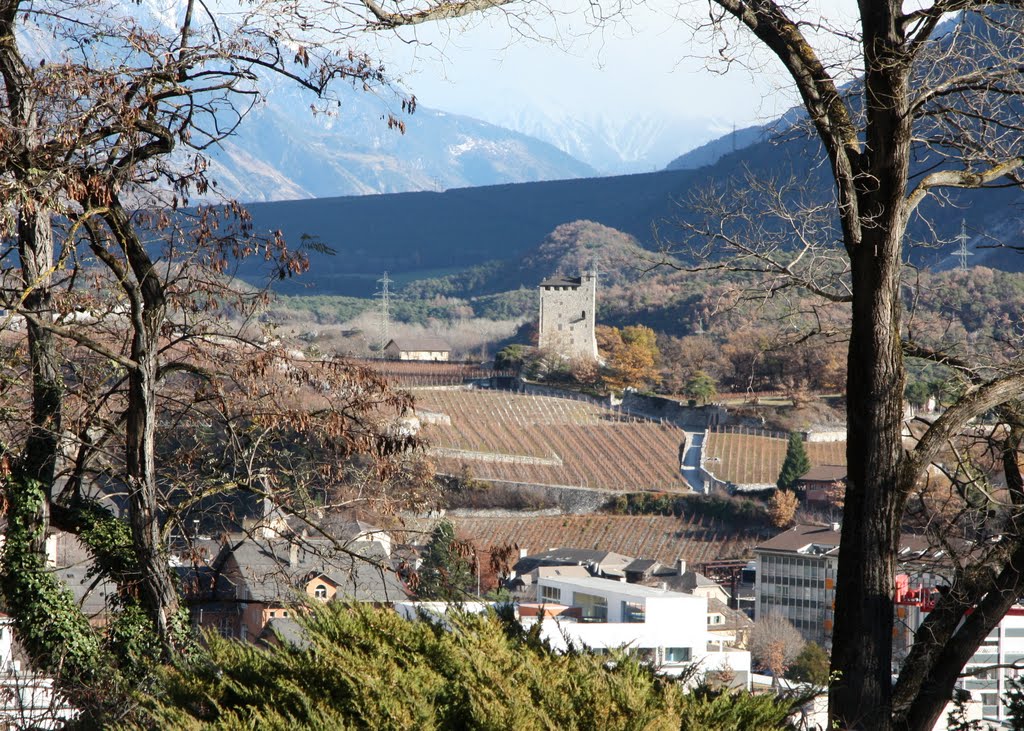

From Salgesch the Rhône transits a liminal zone — for cars and trains it’s through a tunnel — before it emerges in Sierre (Siders) and francophone Valais. The past corrections of the Rhône are well defined here: fortified levees, a made-to-measure width, and a straight course through the valley. It’s also here that one is struck by the sheer number of vineyards visible from its banks: the majestic sweep of the Bernunes slope, the hill of Goubing with its medieval tower (Fig. 3), and the steep vineyards above the city surrounding the landmark Château Mercier.

This is also where the complexity of the Valais terroir first reveals itself. The limestone underlayment of Salgesch extends into the Bernunes villages where it transitions into the famous schist of Valais. This crumbly, marly schist is very near the surface in many spots and is a visible and tactile feature of the landscape.

From the city of Sierre the river glides past the Coteaux de Sierre, a patchwork of schist and limestone, until it reaches the village of Saint-Léonard with its lonely patch of gypsum. The Clos de Mangold is located here, a well-known source for great old-vines chasselas that is consistently among the best in Switzerland.

Not much is made of the vineyards on the Rhône’s left bank, but there are a few of them across from Sierre at Chippis, and some farther along at Chalais and Grône. There is a gathering consensus among growers that this side of the river is under-exploited and may suit cool-climate varieties better than the warm, sun-drenched right bank. It’s also in this area that the ancient variety plantscher once thrived — perhaps, it will again. This is an area to watch.

Not far downstream from Saint-Léonard are the stunning dry-stone walls of Clavau and the twin rock towers of Tourbillon and Valère. This is the picture postcard vista of Sion everyone knows and a reminder of its medieval and ecclesiastical past.

Not far to the east is the Lentine slope, a glacial moraine best known for syrah, marsanne and chasselas (fendant) — each of which is eligible for Grand Cru Sion status.

The vineyards of Mont Orge are at the western limit of Sion and home to the iconic Clos Corbassières (Fig. 4), a wildly terraced vineyard complete with its own bisse. It is one of the signature vineyards of Valais.

Directly across the river are the vineyards and orchards of Bramois, a mixed-farm area better known for its quarry and the role it played in building the great stone walls of Sion.

The central Valais villages of Conthey, Vétroz, Ardon, Chamoson, and Leytron on the right bank, and Riddes — once known for apricots — on the left bank, appear like stops on a metro line. Each seems to have its own special variety to showcase: at Vétroz, for example, it’s the uniquely Valais grape, amigne; at Chamoson it’s sylvaner (johannisburg) — the only commune to celebrate this underrated variety as a Grand Cru; at Leytron both humagne blanche and rouge share highest honors; and Conthey is celebrated as one of only two communes to give the variety savagnin Grand Cru status — Visperterminen is the other.

While most of the landscape so far has featured terraced vineyards, the vast alluvial cone that fans out from the village of Chamoson comes as something of a shock. It has a completely different look from the rest of Valais because the slope is gentle here with none of the terraces that are so emblematic of the region. Chamoson bucked the trend after phylloxera to move the vineyards to higher ground. Today they come right to the river’s edge.

In lower Valais, at Saillon, there is an important geological collision of limestone, schist and gneiss. Gneiss is the main feature of this part of the valley and an important part of the Fully terroir. Gneiss is considered essential to the nervy, mineral character of petite arvine from this end of the valley. In my opinion it is petite arvine’s highest expression.

Across the river on the left bank are the increasingly important vineyards of Saxon and Charrat. The excellent vigneronnes Marie-Thérèse Chappaz and Valentina Andrei both source grapes from these villages.

Martigny is uniquely situated on the left bank of the Rhône but with a full southeast exposure. These are magnificent vineyards with an ancient history that are slightly off the beaten track. There is much terracing here and a tradition of dry stone wall construction that is kept alive by the efforts of local vigneron Gérald Besse. The vineyards of Martigny are among the oldest in Valais but receive considerably less attention than those of the right bank.

Vaud

At Martigny the river bends sharply to the north and the changing landscape is without vineyards for a short stretch until Lavey in canton Vaud (right bank), across the river from the fortified town of St. Maurice (Valais). This area, known as Chablais, includes the wine villages of Bex, Ollon, Aigle, Yvorne and Villeneuve. Mineral, flinty and frequently long-lived chasselas are the standard issue here, but there are a few red specialties as well, including pinot noir, gamay, gamaret, and merlot.

From Villeneuve the Rhône’s life as a lake begins. For those not convinced that Lake Geneva (Lac Léman) is a product of the Rhône, consider this: at least 70% of the lake’s massive volume comes from the Rhône and by some complicated calculations it takes ten years for the water that enters near Villeneuve to exit in Geneva. And if you are wondering why the water is so clear when it leaves the lake, now you know the sediment has had a good long time to settle.

On a sunny day while standing in any of the lakeside vineyards of Vaud one begins to understand the importance of reflected light and the miracle of photosynthesis. Without the influences of the Rhône and Lake Geneva it would be difficult to consistently ripen fruit on its slopes.

At the eastern end of the lake the urban agglomeration of Montreux-Vevey creates a break in the vineyards until just past Vevey at Chardonne. This is the eastern edge of Lavaux.

The Lavaux vineyards are immediately recognizable as some of the most steeply terraced in the world. Most impressive along this length is the stately “Sistine Chapel of Chasselas” at Dézaley. It is one of the most beautiful vineyards anywhere, especially when viewed from a paddle steamer off-shore with a glass of wine in hand. It’s remarkable to contemplate the work involved to not only build such a magnificent vineyard but to maintain and work it. What an incredible source of pride for those who do.

Other sites as you paddle along are the vineyards of Calamin, formed from an ancient landslide, and the gorgeous lakeside villages of St. Saphorin, Cully and Villette. The important wine village of Epesses lies farther up the slope.

On the other side of Lausanne are the more modestly inclined vineyards of La Côte. Chasselas is still dominant here but its expression is slightly more fruity and less saline.

There are twelve areas of production in La Côte, the most prominent of which is Féchy, but all benefit from proximity to the water for light and modulated temperatures. For those unfamiliar with labeling customs in Vaud, when a wine is made from chasselas, only the area of production appears on the label. When made from anything other than chasselas the variety must be named as well.

As a lateral moraine that runs somewhat parallel to the Jura chain, La Côte gradually flattens as it approaches Geneva. This area of production is Nyon which is the second largest area of La Côte and the one closest to the lake.

Geneva

The first vineyards of Geneva are visible even before you leave Vaud. These are found in the exclave of Céligny, a swatch of land belonging to Geneva but surrounded by Vaud and the Nyon production area. Once across the canton’s border the vineyards of Genthod appear, although they seem out of place amidst the mansions and elegant lakeside villas.

The canton of Geneva is divided into three vineyard areas (four if you consider the zones franches separately): The Mandement includes the right bank of the Rhône including Céligny and Genthod; Entre Rhône et Arve is the area between the two rivers; and Entre Arve et Lac is the area between the Arve and the lake.

All three regions are part of the molasse basin of central Switzerland but each is distinct in its soil profile. In some areas the mother rock rises to the vineyard surface or lies just beneath the top soil. In others it is buried by meters of glacial debris or lucustrine deposits. There is sand and fine crystalline sediments from the Arve and Mont Blanc and limestone debris delivered by ancient torrents from the Jura. In other words, Geneva is a jumble of soil types and exposures.

The lake itself modulates temperatures and the entire area is protected from the worst storms by the convergence of the Jura and the Alps.

The Mandement corresponds to the holdings of the Bishop of Geneva before it was reunited with the Geneva Republic in 1536. It includes the villages of Céligny, Genthod, Satigny, Peney, Peissy, Russin, and Dardagny. All are located along the course of the Rhône. The best wines of Geneva come from these villages, which, I dare say, are the most interesting from a terroir point of view. There also seems to be more investment here and a higher level of professionalism. Creeping urbanization is not yet a threat.

The Entre Rhône et Arve area has several wine villages of importance including Bernex, Laconnex, Lully, and Soral. It’s much more of a mixed-use area than the Mandement with housing, industry and open space all in competition with patchy vineyards. There are some interesting producers here but the vineyards tend to be flatter and more amenable to mechanization.

The Entre Arve et Lac area is essentially the left bank of Lake Geneva. It includes the villages of Cologny, Corsier, Meinier, Choulex, Jussy, Gy, Anières, and Hermance all of which are increasingly threatened by housing and development. The vineyards here are patchy and there is a tradition of mixed-farming, including husbandry. I think this lack of focus is a detriment to the wine. I’m not a big fan of the wine from this area, with a few exceptions, even though these vineyards are the ones closest to my home.

The Rhône’s run in Switzerland ends near the village of Chancy. From there it descends into the wine regions of Savoie and Ain and then on to the famous places all wine lovers know.

It’s my hope that knowing a little more about what comes before them will make the entire experience of investigating this wonderful river just a bit more colorful.

Discover more from artisanswiss

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

What a great piece! I’m new to the website but it seems that I’ll stay longer.

LikeLike

Wow!! It’s so pretty. Thanks for sharing wonderful post. I love wine.

LikeLike

Happy you enjoyed it. Thanks for reading.

LikeLike

Thank-you for the excellent in-depth trip along the Rhone! I knew about excellent chasselas, but was surprised to learn about the petite arvine, sylvaner and all the indigenous varieties! I’ve only been to Switzerland in 1986 and remember all the hills being covered in vines. It surprised me, as I had not known it to be a wine region. I used this map to help me follow your trip: http://www.mappery.com/map-of/Switzerland-Vineyards-Map

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments and what a great map. I haven’t seen this one before. Switzerland surprises a lot of people with the amount of wine made and consumed. Cheers.

LikeLike

Another beautiful tour, reminding me of growing up in Geneva, actually in the Mandemant area. I have visited the Rhône glacier, and have noticed how it has receded over the years. The route of the Rhône river in the Valais was nicely described. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks very much Pio. I’m glad you are enjoying the tour. Cheers.

LikeLike